by Neil Partrick

Ian Dobson has been a folk music performer, gig organiser and sound engineer for more than half a century. While for much of his professional career Ian was by day a teacher, by night he was the singer in several notable folk groups. For much of the 1970s and early ‘80s Ian also co-ran a Sussex folk club that hosted both major league and up and coming acts. When he and the late folk musician John Towner took over The Black Horse folk club in Telham near Battle, it became a focal point for both the burgeoning Hastings music scene and a venue for some of the biggest names in British and Irish folk music.

As well as having made his own important musical contribution via The Mariners, The Telham Tinkers and Titus, Ian Dobson takes a scholarly interest in the way that ‘folk’ has been politically and culturally appropriated. As an undergraduate in the mid-1970s Ian wrote a thesis on ‘The Origins and Development of the Folk Clubs in Britain’. Among the carefully constructed interviews with folk club organisers and performers in the files that Ian kindly lent me, I almost expected to find one that the then Manchester Polytechnic student had conducted with himself. He could easily and deservedly have written himself into his own academic script.

Ian Dobson has been a folk music performer, gig organiser and sound engineer for more than half a century. While for much of his professional career Ian was by day a teacher, by night he was the singer in several notable folk groups. For much of the 1970s and early ‘80s Ian also co-ran a Sussex folk club that hosted both major league and up and coming acts. When he and the late folk musician John Towner took over The Black Horse folk club in Telham near Battle, it became a focal point for both the burgeoning Hastings music scene and a venue for some of the biggest names in British and Irish folk music.

As well as having made his own important musical contribution via The Mariners, The Telham Tinkers and Titus, Ian Dobson takes a scholarly interest in the way that ‘folk’ has been politically and culturally appropriated. As an undergraduate in the mid-1970s Ian wrote a thesis on ‘The Origins and Development of the Folk Clubs in Britain’. Among the carefully constructed interviews with folk club organisers and performers in the files that Ian kindly lent me, I almost expected to find one that the then Manchester Polytechnic student had conducted with himself. He could easily and deservedly have written himself into his own academic script.

|

| Ian Dobson & Karen Towner at The Black Horse in October 2019 |

Talking to Ian (and Karen Towner, wife of John Towner) in The Black Horse I got a strong sense what it would have been like for John and Ian when the folk club functioned out of a small room that now houses the pub’s dining section. Ian, on vocals and harmonica, John Towner on vocals, autoharp, whistle and guitar, Ted Bishop on vocals, banjo and guitar, Geoff Marchant on guitar and vocals, George Copeland on bass, and, from time to time, Garry Blakeley and John Burgess, both on fiddle, constituted The Mariners: the musical heart of the Black Horse folk club. The Mariners were all accomplished musicians and renowned for their excellent harmonies. Between songs, Ian and John's banter kept the audience entertained.

Ian first got involved in The Black Horse folk club in 1970 when he and John, with the rest of The Mariners, took it over from Mick Marchant and John Goldsmith, a singing duo who, says Ian, played trad material and some Kingston Trio songs. The Mariners often played a Saturday night residence, while Ian Dobson and John Towner also handled the Black Horse folk club’s administration, initially charging a 20p admission fee. John Towner was, in effect, ‘club chairman and I,’ says Ian, was ‘his lieutenant.’ Together they booked various acts to play at the club, including some that went on to acquire legendary status in the folk world and beyond, such as June Tabor, Martin Carthy, The Dransfields, and folk comedian and regular TV performer Jake Thackray. Proximity to Hastings meant that the seaside musical mecca was a supply line for both acts and punters, but the Telham club was by no means restricted to the local metropolis.

Guitarist Davey Graham once played at The Black Horse in Telham, recalls Ian, noting how ‘detached’ the revered musician was. ‘He wasn’t interested in entertaining the audience,’ Ian remembers. It was as if he just wanted to work out his raga-influenced material. Irish music legend Christy Moore played at The Black Horse too. ‘He turned up in a cloud of dust,’ said Ian, describing the renowned singer’s late arrival outside the pub. ‘He was always late….. He (Christy) got out of his car, looking like a navvy. He was quite gutty due to beer drinking,’ Ian remembers. When an audience member heckled ‘that stomach should be on a woman,’ Christy replied, “Well it was on a woman last night. Make something out of that!”’ Ian notes that Christy Moore could be ‘rollicking one minute and then could entirely still the audience the next.’ Audiences could be very noisy at The Black Horse, like other folk venues, Ian remembers. An amiable group of young farmers would for example prop up the bar and shout out requests, but they could politely be asked to keep it down when the mood required it. Ian remembers that certain performers, such as Martin Carthy, would command total attention anyway; others were designed to be more of a good time act.

Ian was no folk novice. Growing up in Scotland, what in England was being referred to as ‘folk music’ was part of the cultural scenery up there, he says. He remembers witnessing his first ‘proper’, paying, folk gig in 1967: Dave and Toni Arthur performing at a youth club in nearby Hollington. That same year Ian joined the armed forces. As luck would have it, the UK Government's decision in 1969 to deploy troops in Northern Ireland in response to Protestant violence against the Catholic community saw a 22-year-old Ian deployed, armed and in uniform, on the streets of Ulster. Although a member of the Royal Green Jackets, the young Ian had not expected to be ‘pulling Irishmen out of their cars.’

Ian was already singing at this point, and found that knowing The Clancy Brothers, The Dubliners and other Irish material actually proved popular with his English comrades. He learned some Irish songs in Dungannon from singer Roy Weir. Perhaps it was because there were 12 Protestant Englishmen to a room in a small barracks holding 120 squaddies that Ian and others’ private performances went down so well. Ian notes the additional irony that The Clancys, The Dubliners and Alex Campbell were hugely influential on many budding English folk musicians during this period. He also notes that some of the 'Irish' songs had simply been reimagined as such. Ian’s theory is that ‘The Wild Rover’, for example, which the Dubliners almost made their own, was originally ‘collected’ from East Anglia at a time when there were many, often well-educated, Irishmen working in England as labourers, says Ian. Luke Kelly (the lead signer) probably picked it up over here and taught the song to the rest of The Dubliners, says Ian.

Ian has little time for the folk world’s obsession with what’s ‘traditional’, and expresses exasperation with ‘all this nonsense’; this imagined ‘traditional’ purity about songs that, as he puts it, somebody at some point wrote! They didn’t come out of nowhere, he asserts, so what does it mean to be labelled ‘traditional’ he asks rhetorically. Often the songs that were ‘collected’ (or expropriated) were the cleaned-up, polite versions of what had been already been constantly reworked rural songs. Renowned English folk anthologist Cecil Sharpe, Ian points out, collected what in the end were ‘respectable songs’ sung by performers that the local vicar had probably had nicely presented to him. This was the ‘folk process’, he says with some irony. The aural tradition, highly subjective in itself, then became fairly meaningless in an age of records and then cassettes; audio recording became the chief way of passing on the so-called tradition, Ian argues. 'Many folk songs are also real poetry,' Ian asserts. ‘ “The last that I heard he was in Montreal, where he died of a broken heart…” That to me is beautiful,’ Ian says (quoting the song 'Willie Moore').

Returning to England after having unexpectedly honing his singing voice in Northern Ireland, Ian connected with John Towner and, having taken over the folk club in Telham, they performed as The Mariners throughout the south. In 1973 The Mariners (including Ian and John) decamped to the Bexhill pub, The York, after disagreeing with The Black Horse landlady’s plans for an all-weekend venue that relegated the folk spots to a Sunday night. Confining the folk club to the night before Monday morning was never going to fly.

At The York pub in Bexhill amongst others, Ian and John booked singer, guitarist and fiddle player Nic Jones to perform. Since those days Jones has acquired something of a cult status, and is held in an almost tragic light because of being seriously injured in a car crash in the early 1980s. At the time Ian and John hadn’t been able to raise enough from the gig at The York to pay Nic the agreed fee. Jones, kindly and principled, refused to take more than £5, even though he had come all the way from Yorkshire for the performance and had to drive back that night. Ian can’t remember if they ever resolved that issue to everyone’s satisfaction.

While Nic Jones was obviously prepared to travel, Ian notes that there were many established northern acts who didn’t need to come south. People like The Watersons didn’t come south, aside from Norma, says Ian. Many of the ‘northern’ folk comedians such as Mike Harding, Paul Brady and Peter Bellamy (the founder of The Young Tradition), Ian saw at Manchester Polytechnic having booked them for the folk club there.

Folk gigs were only staged at The York pub in Bexhill for a few months. Emblematic of the difference in outlook was the fact that one day the landlord covered the entire pub in tin foil. ‘For acoustic effect?’ I wondered. No, a corny attempt at creating a disco look, clarified Ian.

Ian and John then got involved in running The Hayloft folk club at Fairlight Cove Hotel (near Hastings). ‘We had Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger perform in 1974,’ Ian recalls. ‘They were terribly serious,’ he says disparagingly. In keeping with MacColl’s politics, they were ‘very prescriptive.’ They laid down conditions about their exact requirements in terms of their set, its precise length etc.

Remembering this led Ian to reflect on the politics of folk. There was, it seems, an unspoken English nationalism behind the desire for something that was, somehow, ‘purely’ English. Ian noted that, in parallel with the Irish nationalism of many Irish folk artists with whom budding English folk musicians like Ian were enamoured, there was the desire for something ‘authentic’, as opposed to what he calls the imported ‘shoo wop baby’ of American pop. Ian also notes though that the overtly political message of the kind that MacColl promoted never took off in Hastings and the surrounding area. In fact Ian wasn't keen on just how prescriptive the whole ethos of Ewan MacColl and his ‘Singers Club’ was. You were barred from singing songs perceived as not belonging to your native culture, he remembers. (MacColl’s musical national exclusivism is also discussed in my profile of Dave Arthur).

MacColl himself was an invention though, asserts Ian, noting that his real name was Jimmy Miller and that he was very much a man of his native Salford and not of the Scotland of his parents that MacColl later adopted as his own. In addition to being a renowned songwriter, MacColl was a playwright and an intellect. ‘He was a bright guy, but a liar,’ says Ian. Ian pointedly noted that MacColl deserted from the army in the war. ‘This somehow, irrationally, annoyed me,’ says Ian. ‘My father had fought throughout the war; he (MacColl) had deserted after a few months.’ Ian had of course served in the army himself and was literally (albeit for just three months) born into army life in Germany.

In a different, and from Ian’s perspective more enjoyable, vein, The Mariners opened for the Orange Blossom Special at The Hayloft in December 1973. The Hayloft's impressive roster during this period also included Julie Felix and John and Sue Kirkpatrick. (John Kirkpatrick was later a member of Steeleye Span and was good friends with founder member Martin Carthy). Ian and John were running The Hayloft in tandem with The Black Horse, each venue drawing good crowds. Eventually John Towner returned to performing at The Black Horse in Telham. Among other performers resident at The Black Horse at the time was the guitarist and mandolin player Johnnie Winch (the one-time musical sparring partner of Kelvin Message). Ian told me that Johnnie was, last he’d heard, living in Germany. (I’ve since been told anonymously that Johnnie’s doing blues shows in Germany and is in fine voice.)

From 1975-77 Ian had been a student at Manchester Polytechnic and had run the folk club there, in addition to performing in Sussex at weekends and in the holidays. Ian went back to singing at The Black Horse when The Hayloft folded in 1976. Ian enjoyed the contrasting folk styles of the performers they put on at both The Hayloft and The Black Horse. The Young Tradition, whose more modern approach to performing folk, says Ian, provided a striking contrast with Rottingdean celebrities, The Copper Family, despite singing much of the same material.

It might be wondered why musicians like Ian and John were putting so much into running, and performing at, local folk venues. It was a question that, as a Manchester Poly undergraduate in the mid-1970s, Ian put to others doing precisely that at venues up and down the country. One respondent said they ran a folk club ‘for the money’, which was presumably not meant seriously. Many, perhaps unsurprisingly, emphasised their love and commitment to the music. In a folk club you could see big names ‘up close and personal,’ said Ian. ‘You could buy them a drink. Maybe they’d even buy you a drink!’ All the respondents to Ian’s questionnaires noted the same trends that dominated the folk clubs with which they were familiar: from an early 1960s revival popularised by American protest singers like Dylan and British ‘politicals’ like MacColl, to the late 1960s/early 70s all-pervasive trend of singer-songwriters, to folk comics from the mid-‘70s.

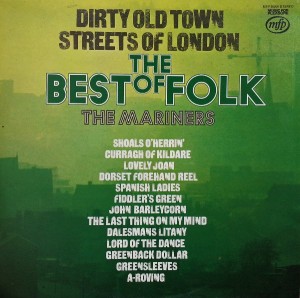

In 1975 EMI released a Mariners’ album to cash in on the folk boom. It was not immodestly titled, ‘The Best of Folk’ and had ‘Streets of London’ and ‘Dirty Ol’ Town’ (pre The Pogues’ cover) emblazoned across the sleeve. EMI initially released the record it via Fanfare Records, and then on the ubiquitous EMI budget imprint ‘MFP’. Some may sneer at the latter, but this helped to ensure that around 50,000 copies of the album got sold.

| The front cover of The Mariners' EMI-released 'Best of Folk' album (Copyright EMI) |

By the time The Mariners had stopped gigging at the end of the ‘70s they had spawned three popular spin-offs: The Telham Tinkers, Plum Duff and Brian Boru. Ian Dobson formed The Telham Tinkers with himself on vocals and harmonica, Ted Bishop on banjo and ‘portable organ’, Pete Titchener on guitar, mandolin and double bass, and Geoff Hutchinson on vocals and guitar. A periodic inclusion was the young Garry Blakeley, who subsequently became a renowned fiddler, including with Steeleye Span. Plum Duff featured John Towner together with Reg Marchant on guitar and mandolin, Tony Davis on guitar and banjo, Colin Baldwin on bass guitar, and Phil Ratcliffe on guitar. (Paul Manktalow was a member for a while too). Brian Boru consisted of the Sedgewick brothers: Peter on guitar and vocals and Paul on uilleann pipes and whistle, and the redoubtable Garry Blakeley on fiddle.

|

| Brian Boru: Garry Blakeley, Paul Sedgewick (foreground) & Peter Sedgewick (right). (Picture taken from the back cover of the 'Folk at the Black Horse' LP, Eron Records. Copyright Eron Enterprises) |

‘Our roadie told us that he “knew a kid who plays a bit of fiddle,”’ remembers Ian. Garry Blakeley was 15 at the time. They asked him to play along to a tune. By the third verse he was musically ‘decorating it,’ says Ian. An uncle from Ireland had taught him mandolin. Gary has for many years featured in ‘A Feast of Fiddles’. He’s chosen to remain round here, says Ian, although he’s had his share of playing in the big league too, having toured with Christy Moore among others. Pete Titchener eventually left for Australia, teaming up with Eric Bogle and also, says Ian, successfully performing as a solo act. Pete was replaced in The Telham Tinkers by Russ Haywood on guitar and Ron Cleave on bass. Ian adds that around this time he was also running a series of gigs and providing PA at Mr Cherry's, a large bar on Hastings seafront.

Some of the musicians who performed in the bands spawned by The Mariners would later embrace a folk-rock orientated sound of the kind that Fairport Convention had pioneered from the late '60s and of which Steeleye Span became one of the biggest exemplars. To Ian’s mind ‘folk-rock’ of this kind was serious. It was utilised by musical scholars of the folk tradition like Martin Carthy who at the same time weren’t afraid of using electric amplification to literally and metaphorically reach a larger audience, often with well-established English folk material. American folk-rock, as pioneered in the mid-‘60s by The Byrds is for Ian an inferior breed, largely encompassing ‘folkish’ styles in an essentially rock format.

The Black Horse in Telham had provided Ian and John with a base for playing residencies whilst they could also bring in other acts to perform such a role, enabling them to gig elsewhere in England and, sometimes, abroad. By the late ‘70s the three Mariners’ spin-offs were playing at different venues every week. Ian calculates that the Telham Tinkers played approximately 250 gigs from 1978 to 1984, many of them on the London and Chichester circuit as well as a short English tour.

|

| The Telham Tinkers. L-R: Geoff Hutchinson, Ian Dobson, Pete Titchener and Ted Bishop. (Picture taken from the back cover of the 'Folk at the Black Horse' LP, Eron Records. Copyright Eron Enterprises) |

The Telham Tinkers, Plum Duff and Brian Boru were all managed by Ron Milner. A Kent tax inspector by day, Ron was a folk impresario who not only helped organise gigs but put money and effort into the release of at least a couple of dozen different albums by English folk acts. These included LPs featuring the three bands, whether as a compilation of all of them (‘Folk at The Black Horse’, Eron) or in their own right e.g. The Telham Tinkers’ ‘Marrowbones’ (Eron 1980) and 'Hot in Alice Springs' (Eron 031, 1981). Both of these Telham Tinkers' albums were produced by Paul Dengate who later formed the local folk-rock band Better Days (who also included some members of Mariners' spin-offs). Limited pressings - Ian estimates that a few thousand each were produced - these LPs could (like the home-produced CDs that accompany almost every pub gig today) be sold at a live spot or used to promote the act. Fhir a Bhata (‘The Boatman’), from The Telham Tinkers' 'Marrowbones', is a fine example of the beautiful harmonies and exquisite musical accompaniment that had also characterised The Mariners. It can be heard here.

Although Ron Milner never gave up his day job, he took the promotion of the Telham Tinkers, Plum Duff and Brian Boru very seriously, says Ian. Ron also ran a folk club in a candle-lit deconsecrated church in Sandwich in Kent. This led to the tongue-twisting ‘Folk In Sandwich’ LP, Ian wryly recalls. The wife of Davey Graham, Holly Gwynne Graham, was managed by Ron and she ended up featuring on the Sandwich club LP too.

|

| Cover of the 'Folk at the Black Horse' LP, circa 1978, Eron Records. Copyright Eron Enterprises |

Ian remembers The Telham Tinkers depping for Brian Boru (named after the former High King of Ireland after all) at a major Irish music venue in London. Ambrose Donahue was the renowned folk agent who organised it. Ian describes it as one of the worst musical experiences of his life. Large, burly Irishmen understandably didn’t take too kindly to a bunch of Englishmen singing them a mix of Irish and American songs. A strange epilogue to his army duties in Northern Ireland perhaps. He remembers the vibe being one of ‘take your money and go’ and that they all felt lucky to have got out in one piece. Although he ruefully recalls that perhaps his attempts at humour may not have helped the situation: ‘Here’s a song by Bob Dylan when he was a young Irishman,’ was apparently one of Ian’s attempts at lightening the mood.

By the turn of the 1980s, the interest in the folk music scene had definitely begun to wane. Ian and Karen put it down to the changes that were already being wrought in the latter ‘70s. Whether it was because of the toughening up of controls on drink driving, the birth of punk that made folk clubs decidedly out of fashion, or the inevitable ageing of those who had become family-orientated folk musicians, there were less punters coming through the doors at The Black Horse and other folk venues. The Telham club continued as weekly event until 1983, Ian and Karen note, while the re-opened Hayloft was to close a year later. In a tragic aside emphasising the fickle nature of ‘popular’ music, Ian notes that Peter Bellamy committed suicide in 1991 because he couldn’t get enough work.

Despite the demise of a number of local folk clubs, Ian and John were as active as ever. In 1980 Ian, Ian’s wife Clare and John formed ‘Titus’. They took their name from a local miscreant Titus Oates. Titus started out performing largely as an acapella trio, Ian says, until Ron Cleave, the guitar and accordion player, joined in 1981, adding instrumental and harmonising depth. Ian notes: 'We were (always) hot on harmonies.’

|

| Titus (Mark 2), with John Towner (left), Ron Cleave, Ian Dobson and Clare Dobson |

Ian expresses sadness but understanding that, after 20 years of loyal service to Titus, in 2002 Ron Cleave retired to the West Country. Mick Mepham, a ‘local rock God’ as Ian cheekily describes him, showed an interest in performing ‘a different kind of music.’ Says Ian, Mick would write songs for the band in a folk style with singable choruses that the audience seemed to appreciate.

Sadly John Towner, Karen’s husband, who had been struggling with ill health for some time, died in 2010. Alan Marshall, whom Ian describes as an excellent guitarist and harmoniser, stepped in almost straight away. Ian’s wife Claire was to die just two years later. Despite suffering from cancer she played a Titus gig only two weeks before she passed away. After Claire died, Titus became a three-piece. In 2014 Steve Cook (a former Better Days member) joined on fiddle, broadening the band's instrumental capability.

In the early days of Titus it had simply been about the enjoyment of playing. ‘There wasn’t the need for the gigs so much at this point,’ said Karen. Titus did though do residencies at The Black Horse in the early days, and at the 1066 Folk Club in Battle. They also performed at social clubs, festivals, political events and PTAs as well as the more regular pub gigs. Ian remembers that Mick Mepham, their main guitarist, moved away to Lincoln but, incredibly, still insisted on carrying on because he was an integral part of the band. This Mick did for two years until he got married and prepared to move to France. However, said Ian, he was still thinking of commuting for gigs! This though marked the end of Titus, and in the spring of 2019, after a career that had spanned nearly 40 years and roughly 500 gigs, they bowed out with a gig at The Jenny Lind pub in Hastings.

Ian and John had also started up the Black Horse Music Festival in 1987, which was held in the pub garden and raised money each year for St Michael’s Hospice. It began when Pete Thomasett, who had been one of the resident musicians at the Black Horse, persuaded the landlord Eddie Dunford to have a reunion gig. Roughly 250 people turned up, including the original founders of The Black Horse folk club, Mick Marchant and John Goldsmith.

‘It was so good that we decided to do it again,’ but we resolved to move it into the pub garden next time, says Ian. ‘Every year it got bigger and bigger; there were bits of Fairport Convention; the Blockheads (minus Ian Dury) played one year.’ It was called ‘The Biggest Little Festival in Britain’, remembers Karen. The musicians performed on the back of trailer, with hay-bails on either side. Friday was blues night; Saturday was the folk night. They had begun purely as a folk festival with Morris dancers, the whole bit. However, remembered Ian, ‘[V]ery soon we realised that we couldn’t sustain this as just a folk festival and got some blues acts.’ There were also some local folk-rock acts such as ‘Better Days’ and ‘The Tabs’ (formerly known as ‘The Tabloid Attitudes’). The Mariners reformed for the festival; Titus were a regular feature. By the 1990s the Black Horse music festival, with a bigger stage and more powerful sound system, had incorporated World Music, although when a Zimbabwean musician’s plane wouldn’t take off from Harare this caused some major panic for Ian, John and the other festival organisers back in Telham. The Black Horse music festival ran for 20 years on the late May bank holiday (at this time Ian would also run the PA for the Jack in the Green Festival in Hastings each May Day weekend).

|

| The 1996 line-up |

The folk element of The Black Horse festival did shrink over time, Ian and Karen concede. Of the former Black Horse resident performers, only some had still survived after all. ‘We did book bigger and bigger folk acts though,’ remembers Karen. Among these were Pete Knight, Steeleye Span’s fiddler, while Norma Waterson and Martin Carthy performed one year. Leon Rosselson played a couple of times. A huge name in the ‘60s folk scene, Alex Campbell, performed too. Folk comics were also on the bill, as they had been when the folk club was running regularly. Stan Arnold, who wrote comedy songs, was a ‘beautiful picker’ says Ian, and interspersed his songs with funny chat. ‘Mr Gladstone’s Bag’ (Dave and Allen Seally) did a set; Brighton comedian (and Jasper Carrot chum) Alan White; and Jeremy Taylor, a public schoolboy kicked out of South Africa for political agitation. In one of his songs Taylor invented the term ‘jobsworth’, says Ian.

The last Black Horse music festival was held in 2009 and, in addition to Titus, its set-list included Abdul-Qader Sadoon from Congo, a Midlands-based Bhangra act, and a number of young local folk and rock-orientated acts. Karen stresses that The Black Horse would still hold the occasional folk night in the old folk club room, with Ian and John (until his untimely death) very much involved. The last Black Horse folk gig was a Christmas charity event in 2016 for St Michael's Hospice.

Ian Dobson is rightly pleased to have played a major role in the promotion and performance of folk and other music in the local area, and to have given The Black Horse and other venues a national, even international platform in the process. Here’s to you Ian.

|

| Ian back at The Black Horse |

Please note that, except where comments are clearly attributed to Ian Dobson or Karen Towner, the opinions contained in this article are entirely those of the author.